Climate Action: All Leaders Great and Small

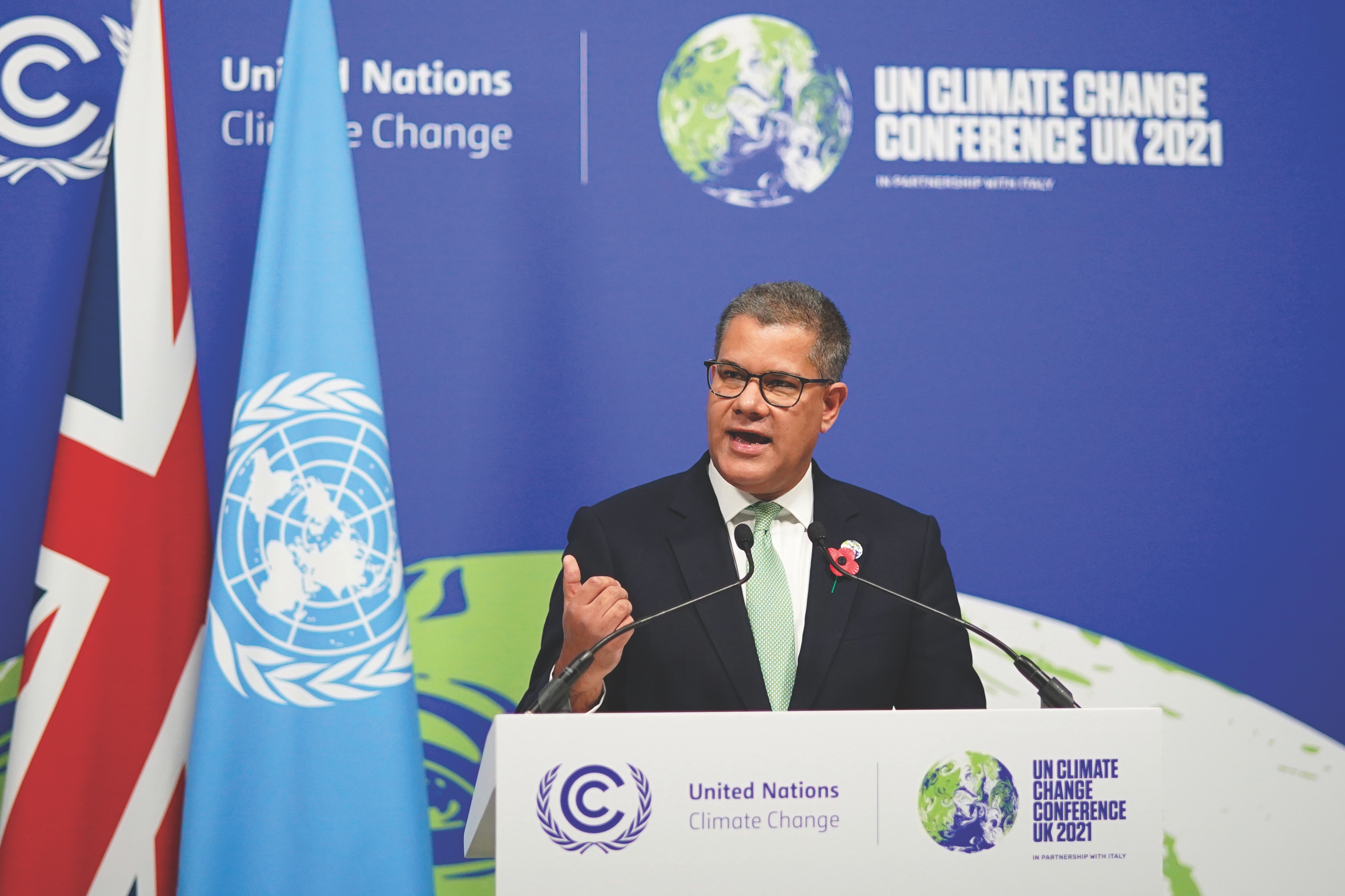

Governance Matters speaks with Alok Sharma, President of the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Heading 6

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript

Since 1995, the United Nations has brought almost every country in the world together once a year to discuss the environment and climate change at a COP, or Conference of the Parties. In November 2021, the UN held its 26th COP, this time in Glasgow, with the summit dubbed the “world’s last best chance” to combat the worst effects of climate change. What distinguished COP26 was not only its importance but its structure: for the first time, non-state actors — city and regional governments, businesses, and nongovernmental organisations — were part of the agenda.

Serving as President for this crucial climate meeting was Alok Sharma, who prior to his appointment had been the U.K.’s Secretary of State for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy. In a recent conversation with Governance Matters, Sharma outlined what COP26 achieved, the steps governments need to take to build on that progress ahead of November’s COP27 in Egypt, and how businesses and local governments are setting the pace and spurring action.

Governance Matters: What did the world achieve at COP26?

Alok Sharma: The first thing to say is that, even in 2021, the geopolitical situation was starting to become pretty fractured — clearly, it has worsened this year. And yet, we managed to get almost 200 countries to sign the historic Glasgow climate pact. One reason countries were willing to do this was that they saw it was in their self-interest; they are feeling the effects and costs of climate change. That is what allowed us, even in those difficult final hours, to deliver this agreement and get a lot of other things over the line.

Over the time we have had the mantle of the COP26 presidency, we have gone from less than 30% of the global economy being covered by the net zero target to more than 90%declaring their commitments.1 And we need to push forward and get more people signed up.

You also saw, for the first time ever at this COP, real representation from non-state actors: businesses, cities, and civil society. They made very clear commitments on things such as limiting coal usage, net-zero transport vehicles, and ending deforestation.

What should governments be focusing on to live up to those pledges you mentioned?

What we got over the line was historic, but these are still words on a page. So, this year is all about delivery.

The first thing is that we have got every country to commit to look again at their 2030 emission reduction targets and come forward with progress by the end of this year. In finance, we want to see more progress made to provide support for countries making the transition. I am reminding governments that they have made commitments for 2030, they have made commitments to go to net zero by the middle of the century, and they’re going to have to deliver during this year, ahead of COP27 in Egypt.

You mentioned non-state actors being involved at COP26. What can cities and local governments do to leverage their agility to continue to lead in the fight against climate change?

We have reached an inflection point where everyone — governments, businesses, civil society — is effectively singing from the same hymn sheet. There are countries I have been to where the business community is pushing faster on net zero than governments are, and by doing so, they’re pulling governments with them. I make a point when I go to different countries to meet with non-state actors, to say to them, “If you are telling your governments that you are willing to embrace net zero and the green agenda, then you are much more likely to see governments move forward and move faster.”

Businesses, in particular, are pushing on this because they’ve worked out, first of all, that it’s the right thing to do. But they have also understood that it is what their clients and customers are increasingly calling for, and that it is good for the bottom line. At COP26, we had the announcement of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero [GFANZ], which saw US$ 130 trillion of private sector money committed towards net zero.2 That is absolutely massive — that represents 40% of all financial assets in the world. And I think that figure will grow.

Just like the private sector, many sub-national governments have decided that this is the right direction in which to go. You have seen more than 1,000 cities, and more than 60 regions, sign up for the Race to Zero campaign [a commitment to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050 at the latest].3 They are driving this forward too. To give you one example, when I went to Brazil in 2021, they were really at the start of the whole net zero discussion. And when I went back there recently this year, 14 states had signed up to net zero commitments. Those states represent 70% of the Brazilian economy. The pace at which non-state actors are driving progress on this is really encouraging.

We need to provide developing nations with support to help them to make that transition, to help them make that leap to clean technologies. - Rt Hon Alok Sharma MP

And on top of that, you have got civil society asking for change. Youth groups in particular were incredibly influential leading up to COP26. One of the reasons we were able to get some things over the line is because of the pressure those groups, alongside civil society, were applying to governments.

How does that momentum continue to build? Do you envision more cross-sector collaboration, particularly public-private partnerships?

We need all kinds of partnerships: between governments, between businesses, between civil society. Everyone is going to have to play their part in driving forward this transition. I mentioned GFANZ earlier; let me give you another example.

A just transition partnership for South Africa was announced at COP26, providing US$ 8.5 billion to help the country transition from coal to clean energy.4 What we want to see during 2022 are more of those public country platform deals announced. In March, I co-chaired a meeting of G7 ministers together with the German G7 presidency. We brought together these countries, multilateral development banks, and private sector money to discuss the question: “How do we work in partnership to help developing nations do the clean energy transition?”

One of the things I have been clear about since I took on this role is that we need to provide developing nations with support to help them to make that transition, to help them make that leap to clean technologies — we cannot say they have to somehow figure out how to do it on their own. And, of course, that requires finance. So, finance is an area where there is plenty of scope for public-private partnerships.

You brought up the just transition. What do you think governments can be doing to restore some of that confidence that the energy transition will be equitable?

If you look at the emission reduction targets that countries have, there will be a proportion of that reduction they can do and fund themselves. And there will be a proportion for which they say they will need support. I would return to this point about increasing the flow of finance. I can tell you we are working with G7 partners on what I hope will be significant country platform deals ahead of COP27. There is a lot of work going on there.

In June I visited South Africa where I met with seven Cabinet Members to discuss the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), and also spoke with current and former coal miners on how the transition away from coal would affect them. A six-month progress report on the South Africa JETP was published following that visit and is available on the COP website.5

As we talk about the just transition, it is also worth discussing the energy transition that is taking place. This is front and centre of everyone’s minds, particularly given Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. There is clearly a link between energy security and a clean energy transition. In the conversations I am having with governments around the world, they are increasingly seeing that the way to ensure domestic energy security, and to have some control over prices, is to have home-grown clean energy.

Climate change is such a complex, global problem that it can leave people — even those heading a government ministry — feeling like it is too big an issue for them to make a meaningful difference. What would your advice to them be?

The first thing I would say is that every government needs to have a whole-of-government approach to this. And you see that increasingly: the prime minister or the president of a country is leading and chairing governmental committees which are bringing forward action on climate.

In the U.K., for instance, we have two Cabinet committees on climate action — one is a strategy committee that the Prime Minister chairs, and the other is an implementation committee that I chair. When you have that leadership from the top, and you have departments working together, it makes a huge difference.

Governments also should be looking to put forward their long-term strategies in terms of how they get to net zero. Again, the U.K. published its net zero strategy at the end of last year ahead of COP26. That is something I would urge every country to do; once you have a plan, you can deliver it.

There is such a big environmental and economic dividend to delivering on net zero commitments. If you keep that in view, you are positioned to come out of this in a really positive direction for your country.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Rt Hon Alok Sharma MP is the President of COP26. As part of his role he chairs the Climate Action Implementation Cabinet Committee, coordinating the U.K. Government’s actions towards net zero by 2050. Between 2019 and 2020, he served as Secretary of State for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy and prior to that as Secretary of State for International Development. He previously held junior ministerial posts in the Department of Work and Pensions, the Department of Communities and Local Government, the Foreign Office, and the Cabinet Office.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.