The Five Roles of an Elite Finance Minister

As higher interest rates, ageing populations, trade turmoil, and spiralling budget deficits make the quality of financial governance more important than ever, Terence Ho and Dinesh Naidu reveal what it takes to be an elite finance minister – and how to build a legacy worth remembering.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Heading 6

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript

Governments Can Make or Break National Prosperity

Throughout history, the mismanagement of government finances has hastened the fall of nations and empires. From the Roman Empire to France under Louis XVI – whose economic mismanagement cost him the French throne and his head – unwise spending, onerous taxation, mismanaged debt, or currency debasement have undermined even the strongest nations.

These lessons are growing in relevance again. Global public debt exceeded US$ 100 trillion in 2024, the equivalent of 93% of global gross domestic product (GDP), and is set to exceed 100% of GDP by 2030, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).1 Around 40% of the world’s population lives in countries where interest payments consume more government spending than education or healthcare.2 Today’s interconnected global economy means that financial contagion can spread rapidly across borders, and amplify the consequences of economic mismanagement. In a polarised political landscape, everything from trade deals and tax rates to labour statistics has become a front-page story.

These acute pressures make the role of a nation’s finance minister more critical than ever. They must manage competing demands from markets, voters and international finance institutions. He or she is required not to assume one role but many, not only to maintain fiscal discipline and steward public resources wisely, but also to shape the economic conditions that will determine their nation’s prosperity for decades to come.

Global Public Debt Surpassed US$ 100 Trillion in 2024

Global public debt in US$ trillion, by region

1. The Steward: Managing the Country Balance Sheet

As the country’s financial steward, the Minister of Finance is responsible for managing and optimising the national balance sheet, from building assets to reducing debt and liabilities. In recent years, many balance sheets have worsened significantly as governments took on more debt, which has left officials with less capacity to direct spending toward education, healthcare, and other priorities.

Declining interest rates since the 1980s have incentivised government borrowing. The 2008 global financial crisis drove borrowing costs to historic lows, where they stayed until the early 2020s.3 Instead of paying down the debts, easy borrowing encouraged many governments to continue running deficits. The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 induced another spike in borrowing to fund healthcare and economic support packages. Subsequent global inflation, and the effect of the Ukraine war on energy prices, drove many governments to extend financial support to their populations, yet again turning to the bond markets to finance budget deficits and further weakening their balance sheets.

Global interest rates remain elevated in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. This has significantly increased the cost of servicing government debt. Governments that have spent decades accumulating debt are now dedicating a growing share of their budgets to interest payments. The interest rate on 10-year U.S. government bonds jumped from about 0.5% in 2020 to over 4% in 2025.4 Governments in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) – a group of mostly wealthy nations – now spend more on servicing interest than on their collective defence budgets.5 The burden is even heavier for low- and middle-income countries, where the cost of borrowing is significantly higher than in high-income countries.6 Developing countries’ net interest payments on debt reached US$ 921 billion in 2024, a 10% increase compared to the previous year, while a record 61 developing countries allocated more than 10% of their government revenues to interest payments.7

Fiscal Guardrails: Rules, Red Lines, and Resilience

Plato observed more than two millennia ago that citizens’ demands for immediate gratification often run counter to the needs of long-term good governance.8 Voters often reward politicians who pledge to expand public spending on popular programmes while punishing those who put up taxes to fund them at the ballot box. This exerts upward pressure on budget deficits, and the finance ministers are often isolated among colleagues in trying to constrain government spending.

Fiscal rules can help finance ministers by stipulating budgetary constraints in legislation or the constitution. Unlike political promises that can be more easily abandoned, these create meaningful, lasting guardrails around national borrowing, with heightened accountability for politicians who break them.

Common fiscal rules include limits on the national debt-to-GDP ratio and budget deficit-to-GDP ratio. Switzerland takes an even more fiscally disciplined approach, by binding the government in law to keep spending in line with projected tax revenues. Limited exceptions are allowed during recessions or national emergencies, but any excess spending must be offset in subsequent years. Switzerland’s public debt in 2025 was only 36% of GDP and falling, compared to 82% in the European Union (EU), and 124% in the U.S.9

Building Assets for Future Generations

On the other side of the balance sheet, Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) have played a growing role in managing financial assets. The assets under management (AUM) of SWFs have increased dramatically in recent years, from US$ 1.2 trillion in 2000 to more than US$ 14 trillion by 2025.10 Like Singapore, which drew down SGD 40 billion of its reserves to meet the COVID-19 crisis, countries with a strong SWF have often been better insulated from recent financial shocks.11

Norway offers a blueprint for putting accountability, integrity, and high performance at the heart of an SWF. The Ministry of Finance has overall responsibility for its management. Its day-to-day operations are carried out by Norges Bank, through its Executive Board, CEO, and Leader Group. There is a broad political consensus on how the SWF should be managed, including a rule that the government should not spend more than the expected return on the fund, which is estimated at around 3% on average.12 These withdrawals from the fund, which managed more than US$ 2 trillion in assets in September 2025, cover around 20% of the government’s annual budget.13

2. The Operator: Delivering High Performance Government

Sprawling bureaucracy, inefficient spending, and sluggish delivery have become the hallmark of government in much of the world. An IMF analysis in 2020 found that roughly a third of global infrastructure spending was wasted due to inefficiencies, rising above 50% in low-income countries.14

As the country’s financial operator, the Minister of Finance is uniquely positioned to strengthen government efficiency through rigorous spending oversight. He or she must put in place sound rules and processes to ensure that public money is collected systematically, spent prudently, and properly accounted for.

Good Data Means Better Results

For finance ministers, promoting greater efficiency starts with ensuring clarity of responsibility and accountability for programme delivery. Frameworks, processes, and capabilities for programme evaluation should be embedded within all government agencies, with the Finance Ministry having overall responsibility to ensure value-for-money in public spending. Programme evaluation helps the Finance Ministry determine if a public programme should be continued, retired, or adjusted.

Finance ministers can perform this role effectively only if they have access to transparent, reliable economic data. Even high-income governments struggle with the data needed for such evaluations. In 2024, 16 federal agencies in the U.S. reported US$ 162 billion in payment errors stemming from data systems that cannot verify recipient eligibility or track spending accurately.15

Reliable and accessible statistics on the country’s GDP, population, employment rate, inflation, and sovereign bond yields give finance ministers the information they need to create evidence-based policy and assess the success of their interventions. These might come from sources including a national statistics office, parliamentary budget office, multilateral institutions, or credit rating agencies.

The challenge for a finance minister is to master this network of institutions and, where necessary, to ensure their finance ministry has the capacity to collate and analyse their findings. Where they have responsibility for managing these institutions, they must also ensure the data they provide is reliable.

3. The Helmsman: Creating the Conditions for Growth

As the economic helmsman, the finance minister leads efforts to grow the economy by encouraging investment and enterprise. The elite minister is the architect of a dynamic marketplace that combines efficient public infrastructure, such as roads and airports, with free-market principles, investment incentives, access to capital, and enlightened trade policies.

This role is critical for governments in an age of widespread disillusionment. The 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer found that in 17 of 28 countries surveyed, a majority of people did not trust their government.16 By promoting economic growth, finance ministers can help to rebuild this trust. Recent research analysing 2.8 million individuals across 161 countries reveals that citizens who experience stronger economic growth consistently report higher trust in their governments.17

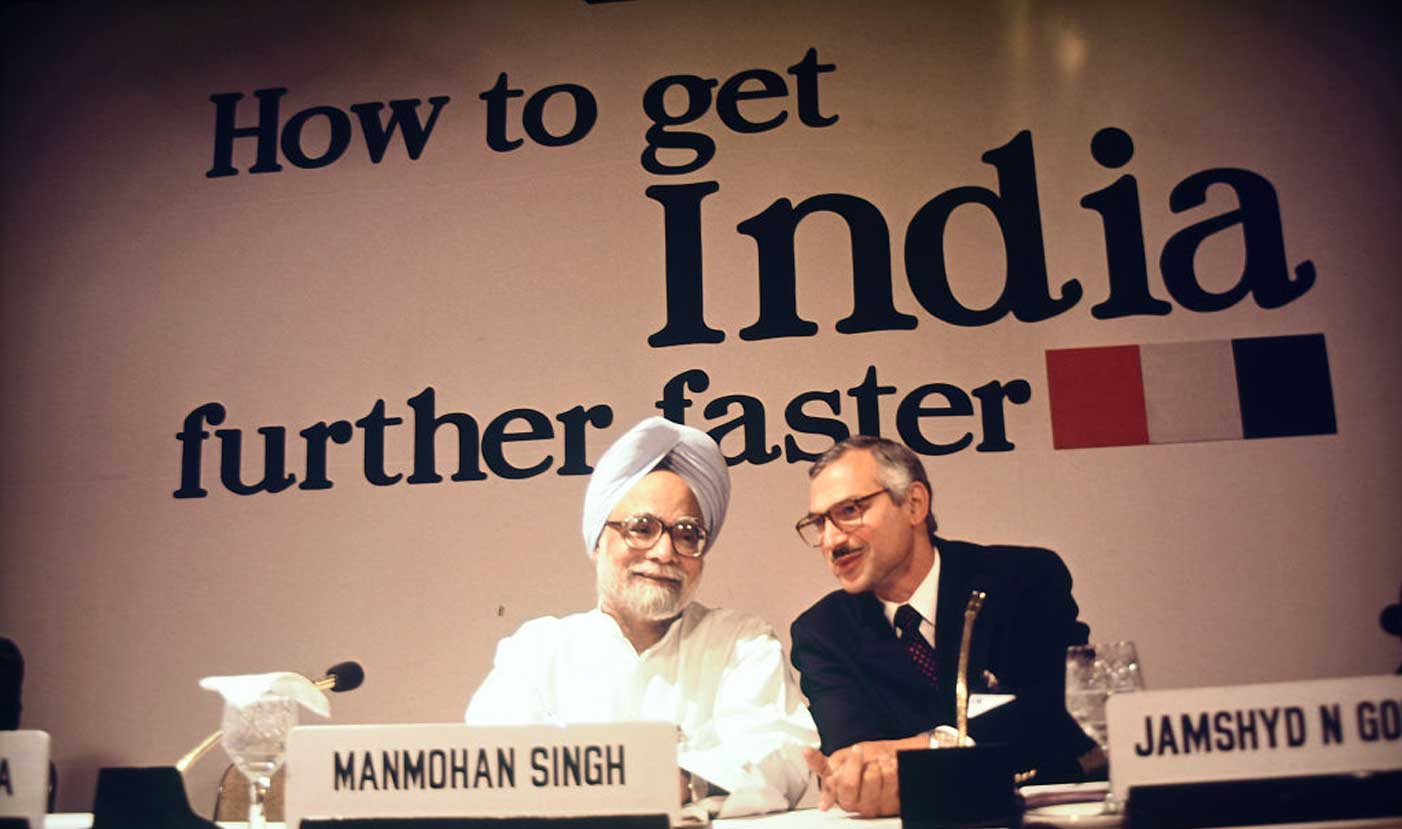

Effective finance ministers understand that economic prosperity often requires dismantling the barriers to business and enterprise. For decades, Indian firms had to secure up to 80 approvals from different agencies before they could expand production or open a new factory.18 As Finance Minister between 1991 and 1996, Manmohan Singh reduced these licensing barriers, limiting government approval to only a few sensitive industries such as defence or hazardous chemicals. This helped to cut red tape while keeping essential safeguards, giving businesses room to grow within a clearer regulatory framework. In doing so, Singh removed a major barrier to growth in India and opened the country to greater international investment.

A nation’s economic strength flows from the scale and strength of its businesses and the vitality of its marketplaces. Creating a strong business sector requires establishing an ecosystem of institutions, regulations, incentives, and infrastructure to support entrepreneurship and growth. Singh, who passed away in 2024, was a visionary helmsman who succeeded in this mission.

Without this anchoring presence, an economy risks drifting in a fast-changing world.

Europe’s Competitiveness Challenge

The European Union (EU) is facing “an existential challenge,” according to Mario Draghi, the former head of the European Central Bank and former Prime Minister of Italy, for its failure over more than two decades to address slow economic growth. Draghi noted the cost in his September 2024 report, The Future of European Competitiveness, “Europe’s households have paid the price in foregone living standards. On a per capita basis, real disposable income has grown almost twice as much in the U.S. as in the EU since 2000.”19

Technology has been the defining industry of the 21st century. “The key driver of the rising productivity gap between the EU and the U.S. has been digital technology – and Europe currently looks set to fall further behind,” said Draghi’s report.

European scientists and entrepreneurs are no less innovative or talented than their American counterparts. They are, however, being held back by the burden of regulation, which 60% of EU companies cite as an obstacle to investment in Draghi’s report. The EU lacks a simple, consistent regulatory framework and a tax system that rewards innovation, productivity, and risk-taking.

Countries that fail to recognise this truth are poorer for it. Capital and talent are mobile – they move from countries with poor governance to countries with good governance. It is the government’s responsibility to position the country as a preferred destination for financial and human capital by establishing a business culture and environment that attracts investment and encourages business creation.

Ray Dalio, a hedge fund manager and author of How Countries Go Broke, argues that this pattern reflects what he calls the “Big Debt Cycle”.20 At first, government borrowing finances productive ventures – shipyards, ports, industries, and armies – that expand trade and generate income to repay loans. Later, governments borrow not to expand but to cover running costs such as military upkeep and civil service pay. Eventually, new debt is used mainly to pay interest on existing loans. At that stage, Dalio notes, lenders grow cautious, demand higher yields, and push borrowing costs higher still. The result is what he calls a “debt death spiral”, where rising interest rates continue to weaken demand for bonds, and drive up the cost of borrowing further.21

To bring debts down to sustainable levels, Dalio argues that governments must reduce their budget deficits through a mix of spending restraint and higher taxes. They must adopt strict fiscal rules to prevent unchecked borrowing. And they must align monetary and fiscal policy so that interest rates support sustainable debt levels rather than destabilise them. Without such measures, Dalio warns, countries face stagnating economies and social unrest – and, like the Dutch Republic, the eclipse of national prosperity that once seemed secure.

4. The Strategist: Creating A Game Plan for the Future

An elite finance minister will also anticipate spending needs arising from demographic, geopolitical, economic, and social trends and plan for revenues and other sources of financing.

Around the world, countries are anchoring their economic strategy in a vision for their nation’s future. An economic vision paints a long-term picture of what a country can become. Singapore is working to build the country into an advanced manufacturing hub by the end of the decade. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 is focused on reducing its dependency on oil and expanding sectors such as tourism, entertainment, and technology. From these frameworks flow policy ideas – investments, tax breaks, deregulation – that make the vision possible. It allows a finance minister to mobilise resources and the public to work towards a common goal.

Since it gained independence in 1971, the UAE’s economy has grown over 500 times, from less than US$ 1 billion to over US$ 500 billion in 2024.23 Like Saudi Arabia, that growth was powered by oil revenues for decades. But over time the government used those revenues to invest heavily in technology, renewable energy, tourism, and finance to diversify its economy. The finance ministry played a critical role in executing that vision, especially by funding the state-of-the-art infrastructure that defines the country in the world’s imagination today, and creating the fiscal frameworks to attract greater international investment. Today, non-oil revenues account for around three-quarters of GDP, evidence of how an economic vision can translate into lasting change.

5. The Risk Manager: Guarding Against the Unknown

The Minister of Finance, as the nation’s risk manager, will be attuned to financial risks from geopolitical and trade tensions, financial contagion, and natural disasters. Fiscal planning should include the provision of a sufficient financial buffer against those risks.

The first half of the 2020s has featured two major international conflicts, in Europe and the Middle East, and a global pandemic. New country alliances are seeking to challenge the U.S.-led world order. The eruption of new military conflicts, pandemics or other man-made or natural disasters could spark financial contagion in an already fragile global economy.

Elite finance ministers use strategic foresight tools to anticipate and prepare for such contingencies. Chief among these is scenario planning, the development of plausible alternative visions of the future, based on key driving forces, trends and uncertainties. The exercise maps out possible scenarios to anticipate and plan for responses to various pathways. To be effective, the timeframe of the scenarios must be defined, and the lessons embedded in policy considerations.

“Back-casting” offers an alternative approach. It begins with the desired outcome and requires the minister to work backwards to design steps and actions required to get there. This is complemented by “road-mapping”, which focuses on how current trends and policy interventions could shape the future. Policies resulting from these exercises must then be stress-tested. This is to make sure they stand the test of real-world conditions and encourage ministers to make them more robust.

The Most Noble Legacy

The coming decades will test finance ministers more severely than any period in recent history. Ministers of Finance will face a balancing act between managing a debt burden and investing in economic competitiveness. Many will have to contend with ageing populations and falling productivity. Their policy choices will echo across generations and determine whether countries stagnate or progress.

Finance ministers who leave behind a stronger fiscal balance sheet, improved economic competitiveness, and a greater national reputation will create the most noble legacy any political leader can leave behind – a prosperous nation for generations to come.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Endnotes

- https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2024/10/15/globalpublic-debt-is-probably-worse-than-it-looks

- https://unctad.org/publication/world-of-debt

- https://data.bis.org/topics/CBPOL/tables-and-dashboards

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/247556/monthlydevelopment-of-ten-year-treasury-security-yield-rates-in-the-us/

- https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2025/03/global-debtreport-2025_bab6b51e.html

- https://unctad.org/publication/world-of-debt

- https://unctad.org/publication/world-of-debt

- https://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.9.viii.html

- https://www.reuters.com/markets/europe/what-rest-worldcan-learn-swiss-exceptionalism-2025-07-15/

- https://globalswf.com/

- https://www.mof.gov.sg/policies/reserves/what-are-thereserves-used-for

- https://www.nbim.no/en/about-us/about-the-fund/

- https://www.swfinstitute.org/profile/598cdaa60124e9f d2d05b9af

- https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2020/09/03/blog090320-how-strong-infrastructure-governance-can-endwaste-in-public-investment

- https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-25-107753

- https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2025-01/2025%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer_Final.pdf

- https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/global-growth-slowdownbad-news-trust-government

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/55427.stm

- https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en

- Dalio, Ray (2018). Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises. Bridgewater Associates.

- https://www.ft.com/content/14e24862-4cc8-4329-8b2e-934e8c30d1c7

- https://x.com/RayDalio/status/1929967582112587868

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=AE

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Terence Ho is Deputy Executive Director and Associate Professor (Practice) at the Institute for Adult Learning, Singapore University of Social Sciences. He is also an adjunct faculty member at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore. From 2002 to 2020, he held research, policy, and leadership roles in the Singapore Public Service, including six and a half years as a director at the Ministry of Finance. Since 2021, he has written four books, including “Future-Ready Governance”, as well as two book chapters. He regularly contributes opinion pieces to media outlets.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Dinesh Naidu is the Director of Knowledge at the Chandler Institute of Governance (CIG). Dinesh has a decade of leadership experience in the Singapore government, where he was responsible for the development and delivery of knowledge products aimed at senior government leaders around the world. At the Centre for Liveable Cities in the Ministry of National Development, his teams developed a range of print and digital publications as well as curated and organised the World Cities Summit, the largest international gathering of Mayors and city leaders.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.