King Ashoka: Lessons in Ethical Governance from an Ancient Indian Ruler

King Ashoka’s reign in ancient India, once marked by conquest and bloodshed, transformed into an era of compassion, peace, and unity after his embrace of the moral philosophy of ahimsa, or non-violence. Historian and author Patrick Olivelle examines what his legacy can teach us about leadership and ethical governance in today’s increasingly polarised world.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Heading 6

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript

Amidst the tens of thousands of names of monarchs that crowd the columns of history, their majesties and graciousnesses and serenities and royal highnesses and the like, the name of Ashoka shines, and shines almost alone, a star.1

That was H. G. Wells’s somewhat hyperbolic assessment of King Ashoka (268–232 BCE), who ruled most of the Indian subcontinent from present-day eastern Afghanistan to Bengal, and from southern Nepal to Karnataka, a state in southwest India. The uniqueness that Wells alludes to is Ashoka’s willingness to admit his mistakes and apologise for the carnage he caused in his victory over Kalinga (largely the eastern state of Odisha in present-day India).

After the brutal war in Kalinga, Ashoka underwent a transformation, an event memorialised in his Rock Edict XIII. He renounced war and territorial expansion and developed a moral philosophy anchored in the virtue of ahimsa – non-injury and non-violence. How he sought to propagate and instill this moral philosophy across his subjects offers timeless lessons in leadership and governance still relevant in our modern era.

Communication is Key – Public Education Through Rock Edicts

Within human societies, especially between leaders and followers, communication is key. This feature may have evolutionary roots. Leaders in ancient times were not simply the strongest and the fastest; they emerged as leaders principally because of their skill in communication, their skill in connecting not just intellectually but also emotionally with members of their groups.

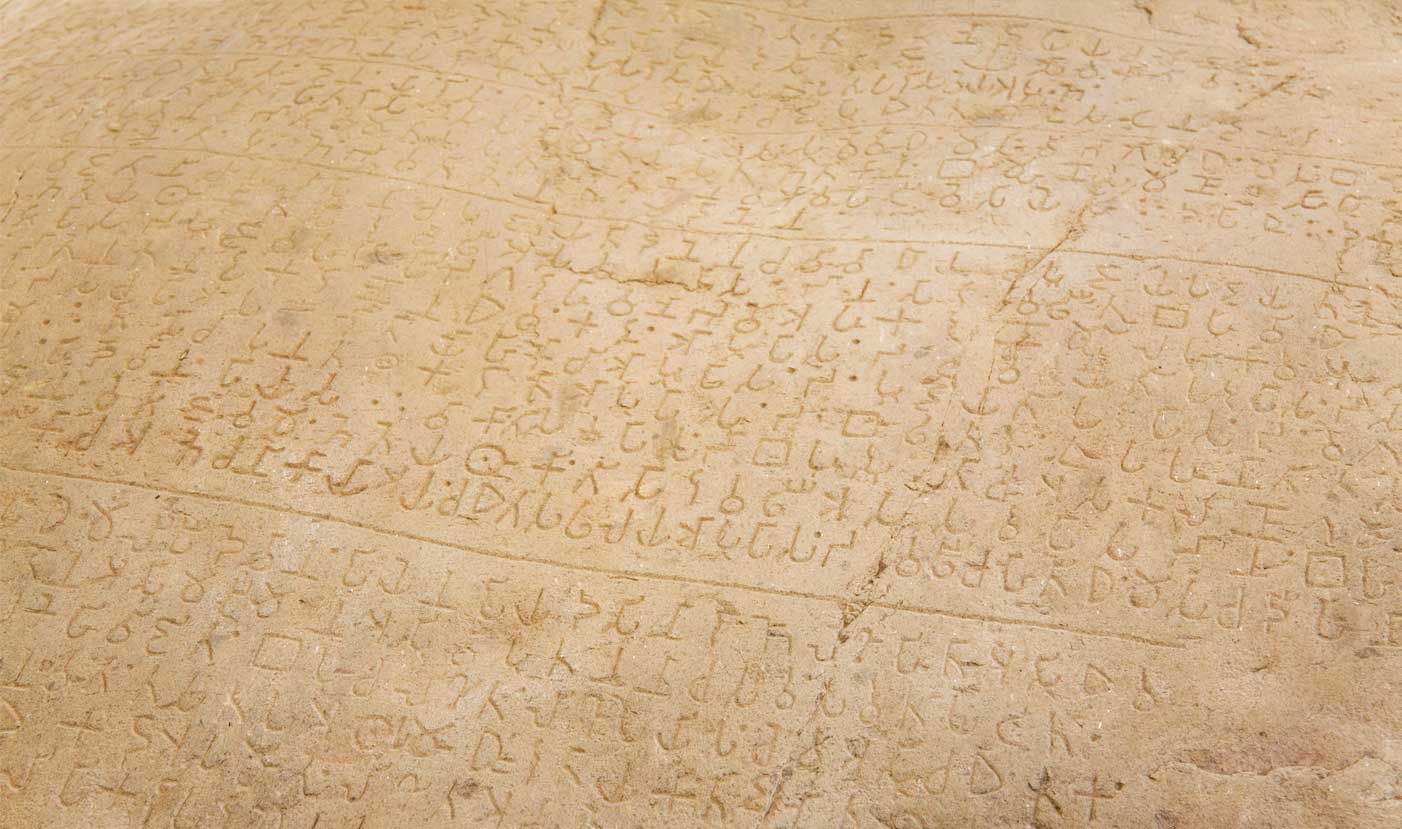

Ashoka was one such charismatic leader. The Rock Edicts were among his most enduring legacies – 14 major monumental inscriptions, alongside a few minor ones, carved on rocks and pillars across the Indian subcontinent that have survived to modern times. These edicts represent one of the earliest written records of Indian history and offer rare insights into the administration, philosophy, and ethical values of Ashoka’s reign.

A World of Religious and Philosophical Plurality and Polarity

A prominent feature of Ashoka’s message was his outreach to religious and philosophical organisations that were diverse and divided.2 He called these organisations Pasandas, consisting of recognisable religious groups with distinct names, ideologies, lifestyles, and perhaps attire. Ashoka tells us that Pasandas were spread throughout his empire, and indeed even outside it. We can take Pasanda to parallel our category of religion, with significant differences. Ashoka mentions four Pasandas by name: Buddhists, Brahmins, Ajivakas, and Jains, but adds that there are others beyond these.

Pasandas are also found even in the Greek states of West Asia left in the wake of Alexander the Great’s invasion and untimely death. The Kandahar II edict, based on Rock Edict XII, translates Pasanda into Greek as diatribé, a term that may have meant at that time a philosophical school, but also a form of rhetoric in which an opponent is attacked in a long critical speech.

Furthermore, Rock Edict XIII says: “There is no land... where human beings are not devoted to one Pasanda or another.” So, it appears that, at least in Ashoka’s mind, there were Pasandas, or diatribés, among the Greek kingdoms of the west, as also in other lands. Ashoka saw Pasandas as transcending political, ethnic, religious, geographical, and linguistic boundaries.

The Pasandas, however, constantly fought with each other. This mutual antagonism is reflected in the pejorative use of Pasanda in later religious literature where it mostly defines the evil other. Antagonism is also embedded in the word diatribé itself when it describes a rant where humor, sarcasm, and appeals to emotion are used in criticising an opponent – oratory tactics that sound all too familiar to observers of modern political discourse.

No gift or homage, however, is as highly prized by the Beloved of Gods as this: namely, that the essential core may increase among all Pasandas. Although cultivating the essential core takes many forms, its root lies in guarding one’s speech – that is to say, not paying homage to one’s own Pasanda and not denigrating the Pasandas of others when there is no occasion, and even when there is an occasion, doing so mildly. (Rock Edict XII)

Ashoka’s Principles of Diplomacy

Guard One’s Tongue

Ashoka’s message of ecumenism to these Pasandas speaks directly to modern challenges of domestic politics, governance, and international relations. The first step involves guarding the tongue. Do not, Ashoka tells the Pasandas, praise your own group nor denigrate others:

The “essential core” here refers to dharma – truth, virtue, correct behaviour – the term that anchored Ashoka’s moral philosophy. Ashoka is counselling the Pasandas to increase their knowledge of and commitment to dharma. Humility and concord among those who have dedicated their lives to dharma are a basic and minimum requirement.

See the Good in Others

Such an attitude requires not only refraining from denigrating other Pasandas but also an active commitment to seeing goodness in them. Ashoka thus continues in Rock Edict VII:

Homage should indeed be paid to the Pasandas of others in one form or another. Acting in this manner, one certainly enhances one’s own Pasanda and also helps the Pasanda of the other.

From a passive stance of not creating conflicts with other Pasandas, we move here to an active stance of engagement with them. The first step of this engagement is seeing something praiseworthy in them.

Listen and Learn

Still, true ecumenism demands not just the minimum: tolerance, living in harmony, not using insulting language. Living an ecumenical life alongside other religions demands that Pasandas converse with others, learn from others, educate themselves in the dharma of others. It requires an activist, positive, and proactive agenda.

Ashoka tells Pasandas that true learning requires listening. You cannot be learned if you do not listen. You cannot learn by simply listening to yourself or to your own group. You have to expand your horizon. You have to talk to and especially listen to other Pasandas.

The implication is profound: each individual Pasanda cannot make its members highly learned in isolation but can do so only through conversations, interactions, and dialogue with members of other Pasandas.

A further implication is that no single Pasanda possesses the complete dharma, the complete truth and the “essential core” described at the very beginning of this edict. It naturally follows that no single Pasanda possesses full knowledge of the path to salvation. That appears to be Ashoka’s ecumenical message to religious practitioners of his time. Ecumenism is not simply a good and honourable side issue; it is essential for the Pasanda quest.

Leadership Lessons

Openness to Diverse Ways of Doing, Thinking, and Being

What would Ashoka have to say to modern-day Pasandas? How will his ecumenical message speak to our modern predicament where human communities are drawn ever closer together by modern technological innovations, while these same technologies push communities apart, and vituperative and demeaning language against each other has been normalised in social media?

Here, we need to extend the parameters of Pasandas to include – besides the world’s multiple religions – political and ideological parties and organisations, and even modern nation states that demand allegiance and promote nationalism.

If we were to create a proverb inspired by Ashoka, a fitting one might be: “No group or individual has a monopoly on truth or virtue.” Ashoka preached a gospel of openness – openness to others, to other ways of thinking, to other ways of being, to other ways of articulating the truth. Be open and be attentive to what others are saying. Listen more and talk less.

Non-Aggression among States

Non-aggression would be a basic and foundational requirement of international relations – the same advice Ashoka gave his sons and grandsons, his future successors.3 4 A fundamental aspect of non-aggression is for nation-states and their leaders to guard their tongues and uphold respect for each other’s culture, language, and opinions.

Such an attitude of humility and cooperation would preclude the common phrases of self-praise and denigration we hear from the leaders of many countries today. According to Ashoka’s sage advice, speech should be a glue to unite and cooperate rather than a cudgel to beat up opponents and a wedge to divide.

Building a Strong Bureaucracy

Ashoka was aware that a strong and effective bureaucracy was essential to both the proper functioning of government and the success of his innovative political and moral philosophy based on dharma. In the 13th year of his reign, he established a new bureaucratic arm consisting of high officials in charge of propagating dharma. He saw this as one of his major achievements. Strengthening and empowering agencies to promote domestic and international governance based on dharma or righteousness would be one further lesson we can draw from Ashoka’s political philosophy.

Fighting the Good Fight

Ashoka’s idealism may be a lost cause today as it was in his time, but it is still a cause worth fighting for. As T. S. Eliot said:

If we take the widest and wisest view of a Cause, there is no such thing as a Lost Cause because there is no such thing as a Gained Cause. We fight for lost causes because we know that our defeat and dismay may be the preface to our successors’ victory, though that victory itself will be temporary; we fight rather to keep something alive than in the expectation that anything will triumph.5

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Endnotes

- Wells, H.G. 1951 (1920). The Outline of History: Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind. Revised edition. London: Cassell.

- Bhargava, Rajeev. 2022. “Ashoka’s Dhamma as a Project of Expansive Moral Hegemony.” In Bridging Two Worlds: Comparing Classical Political Thought and Statecraft in China and India, eds. Amitav Acharya et al. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Olivelle, Patrick. 2022. “Mining the Past to Construct the Present: Some Methodological Considerations from India.” In Bridging Two Worlds: Comparing Classical Political Thought and Statecraft in China and India, ed. Amitav Acharya et al. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Author’s note: I deal with these elements of Ashoka’s moral philosophy in Patrick Olivelle 2024. Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Eliot, T.S. 1932. Francis Herbert Bradley in His Selected Essays, 1917–1932.

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Patrick Olivelle is Professor Emeritus of Asian Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. His recent publication, “Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King” (HarperCollins and Yale, 2024), has been translated into German and French and was reviewed in the Wall Street Journal and Le Monde. It was listed as one of the “Best Books of 2024” by The New Yorker. Professor Olivelle was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and awarded an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters by the University of Chicago in 2016, as well as a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1996. He holds a Master’s degree from Oxford University and a Doctor of Philosophy degree from the University of Pennsylvania.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.