Imitation, Innovation, and Optimism: Lessons in Governance from the Golden Ages

Historian Johan Norberg reveals how imitation and openness shaped history’s greatest civilisations, and what practitioners today can learn from their triumphs and tragic missteps.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Heading 6

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript

We call them golden ages – the creative explosions that arise in unexpected corners of history, from ancient Athens and Rome, the Abbasid Caliphate and Song China to Renaissance Italy, the Dutch Republic, and the Anglosphere.

Among the many lessons these periods offer our own era, some of the most revealing concern their governance. The most effective leaders are not those who have all the answers, but instead those who construct the frameworks through which others may find them. They build feedback loops that enable societies to learn quickly from both success and failure, rather than pretending to possess perfect foresight. It is this that enables cultures to remain adaptive, innovative, and resilient in the face of great challenges.

When we speak of golden ages in history it is important to remember that they were not golden for all. As the classicist Mary Beard has remarked, those who express admiration for the Roman Empire invariably imagine themselves as emperors or senators – a few hundred privileged individuals – rather than as the enslaved millions working in mines, plantations or other people’s households.

Yet slavery and oppression were not what made these civilisations distinctive. Such injustices have, tragically, been the rule rather than the exception throughout history. These would not have surprised their civilisational neighbours. What distinguished golden ages was that, for a brief moment, these societies rose above the norm and achieved living standards and human flourishing that impressed their contemporaries – and often the subsequent generations.

How did they achieve this? Through imitation and innovation.

The Art of Imitation

Golden ages often begin not in originality, but in borrowing. These civilisations did not develop all the ideas and technologies that drove their ascent; rather, they absorbed them from others. They often emerged at crossroads between cultures, and they listened carefully to merchants, migrants, and missionaries who brought with them foreign ideas and methods. Often, like the Athenians, the Dutch or the British, they were maritime societies that collected new knowledge on their business trips abroad.

Others, such as the Abbasid caliphs in ninth-century Baghdad, institutionalised intellectual openness by inviting scholars from other cultures and faiths, and by translating their texts into Arabic. Renaissance Italians similarly found inspiration when they rediscovered ancient texts hidden away in monastic libraries across Europe.

The Romans, for all their brutality, developed a system that continually absorbed the talents, ideas, and technologies of the peoples they conquered. In the first century A.D., Emperor Claudius argued that Rome had risen to power not merely by defeating other peoples, but by mastering the art of fighting and naturalising them on the same day. A vanquished foe could pursue a second career in the army or even the Senate if they had sufficient ambition and aptitude.

The great leaders of the golden ages encouraged their people to look beyond their comfort zones in search of better methods. The Song emperors of China in the 11th century promoted agricultural innovation by publishing manuals on improved techniques and new crops. In less literate regions, they placed illustrated instructions on the walls of government offices to show how land could be used more productively.

Instead of imposing their own ideas from the top down, golden age societies found ways to unlock knowledge from the bottom up

Great Leaders Crowdsource Innovation

They also promoted pluralism, ensuring that a broader range of methods, discoveries, and perspectives became available – even some that might make the rulers themselves uncomfortable. One unconventional reform introduced by the first Song emperor was to avoid executing officials who disagreed with him. This helped to break the institutional habit of promoting yes-men and instead encouraged “friends with arguments” to challenge and refine his thinking.

To secure popular support for continual change, leaders also had to foster a culture that embraced it, and to establish a system of rules within which individuals could experiment freely. There had to be some well-understood limits. Claudius, for example, told the Senate that the Gauls were now ready to be integrated into Roman society because “they no longer wore trousers” – trousers being a barbaric sartorial choice according to toga-wearing Romans.

Openness gave these societies access to more minds and more methods. But imitation alone could only take them so far. To create a truly self-sustaining golden age, they had to combine foreign inputs with local ingenuity to produce genuine breakthroughs – whether in agriculture, art or administration. This always needed a measure of economic freedom and some constraint on the arbitrary power of rulers. Instead of imposing their own ideas from the top down, golden age societies found ways to unlock knowledge from the bottom up – from communities, officials, and entrepreneurs. In effect, they crowdsourced solutions.

Crises Spark Breakthroughs

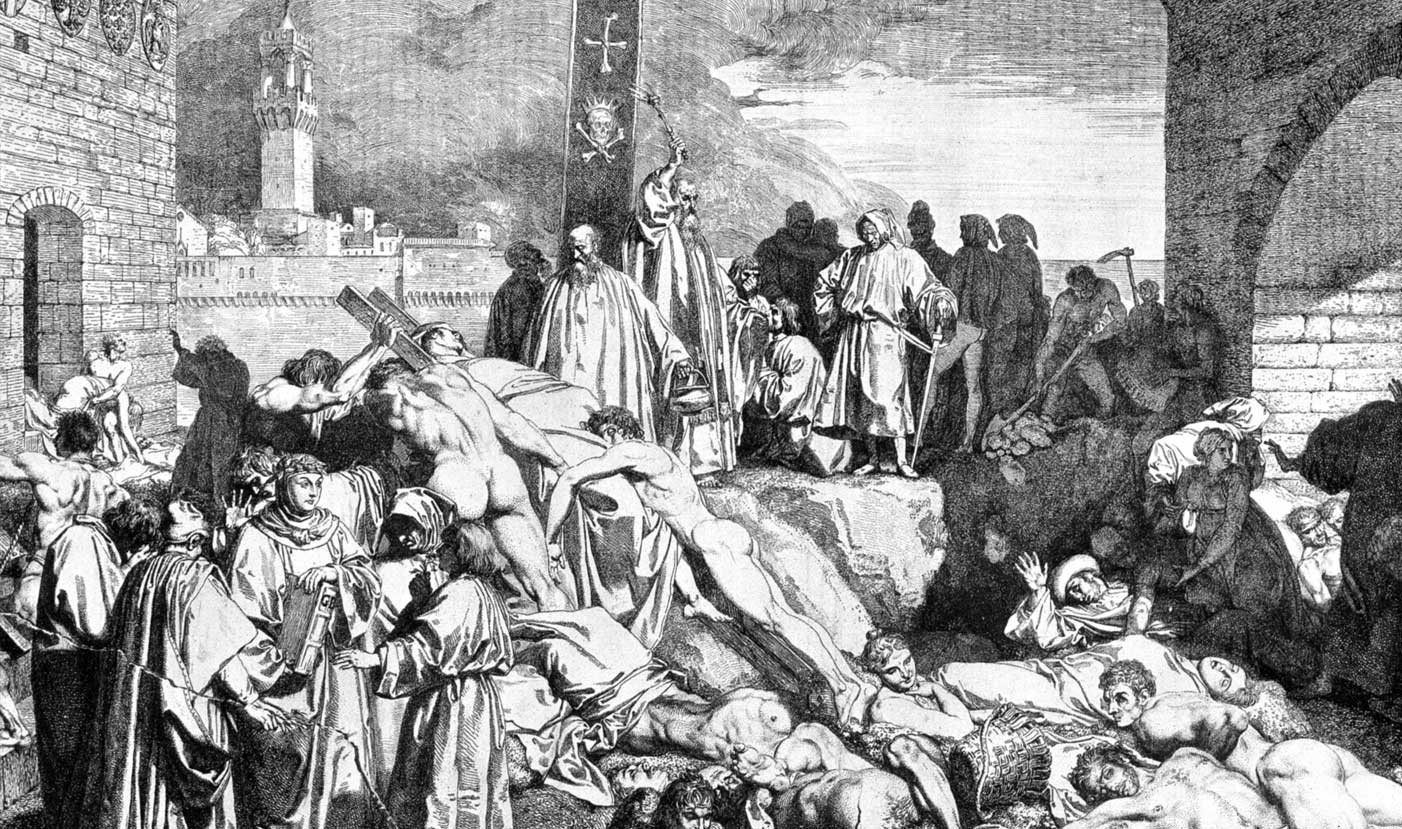

This kind of decentralised discovery was not simply a by-product of prosperous times: it was often a response to crisis. In the aftermath of the Black Death in the 14th century, surviving city-states in northern Italy did not concentrate power – but instead devolved it. Guilds, universities, and merchant associations were given room to test new forms of organisation and even alternative legal systems. Rather than trying to plan their way to recovery, they experimented their way there, and that resilience laid the foundations for both economic growth and artistic revival.

Each of these golden ages faced a crisis in which they turned against the openness that had previously defined them.

Enlightenment thinkers in the 17th and 18th centuries did something similar after the religious wars that had torn Europe apart. From transnational scholarly correspondence to scientific academies and coffeehouse debates in Amsterdam, Paris, London, and Edinburgh, they created ecosystems in which disagreement was not feared but embraced as a catalyst. And from these networks emerged the revolutions in science, technology, and civil liberties that helped shape the modern world.

The Dutch Republic succeeded in wresting its independence from the mightiest empire of the 17th century, Habsburg Spain, while simultaneously cultivating a remarkable artistic, financial, and scientific culture – due precisely to starting with so little. Lacking a standing army, a navy, established universities or artistic traditions, and with scarcely any arable land to sustain their population, the Dutch were compelled to innovate their way around these constraints. In doing so, they became more open and outward-looking than perhaps any other people of the era.

In hindsight, it is often the constraints, not the comforts, which drive the most profound breakthroughs. Habsburg Spain, with precious metal from its American colonies, had it all. Yet it had to declare state bankruptcy again and again. Conversely, instead of stifling progress, adversity often sharpens ingenuity. Like the Dutch reclaiming farmland from the sea, or Renaissance thinkers reconstructing knowledge from scattered texts and stumbling on novel and pioneering interpretations, limitations became invitations to think differently. The very struggle to overcome natural or institutional constraints has often catalysed the greatest leaps.

Hope Breeds Dynamism

History has shown that progress can become self-perpetuating beyond a point, as it reshapes how people understand themselves. Innovation is difficult, controversial, and uncertain. For it to take root, a society must have a hopeful outlook on the future, and role models who have shown that transformation is possible. These are the figures from whom others draw inspiration, knowledge, and the motivation to try.

That is why we so often see creative clusters: philosophy in Athens, classical music in Vienna, technology in Silicon Valley, and art in Renaissance Florence. In city-states like Florence, a dynamic interplay between Church patronage, banking networks, and artists’ guilds enabled innovation in both finance and fresco. Michelangelo accused Leonardo da Vinci of being a procrastinator who never completed his works, while Leonardo criticised Michelangelo’s overly muscular figures as looking like “sacks of walnuts.” They were both right, and their rivalry pushed them to create some of history’s greatest masterpieces.

The Warning Signs of Societal Decline

Pessimism, by contrast, is paralysing. A belief in inevitable decline becomes self-fulfilling. Why strive if failure is assured? This is one of the earliest signs of the decline of a golden age.

Elites who have benefitted from innovation often try to kick away the ladder behind them. Groups unsettled by change attempt to fossilise culture into orthodoxy. Predatory neighbours, attracted by success, seek to seize its spoils. The most dangerous threat, however, comes from within.

In times of uncertainty, we tend to seek stability and predictability, shutting out anything unfamiliar or unpredictable. Each of these golden ages faced a “death-to-Socrates” moment – a crisis in which they turned against the openness that had previously defined them. They embraced strongmen, tightened controls over the economy, and withdrew from international exchange. This fear of disaster became self-fulfilling: by closing themselves off, they lost access to ideas and resources that might have helped them adapt.

Rome began its decline as early as the third century, when it abandoned religious pluralism and emperors took more direct control of the provinces and markets. Cities became increasingly dependent on imperial bureaucracy and lost the ability to adapt. The barbarian invasions that followed were the coup de grâce, but the empire had already eroded from within and lost its ability to withstand them. Like Hemingway’s description of bankruptcy, Rome fell in two ways, first gradually, then suddenly.

China’s golden age ended when the Ming emperors, in the 14th century, tried to revive an idealised version of the country’s past by banning international trade and intellectual openness. They even forced citizens to adopt the clothing styles of four centuries earlier. The result was the dismantling of the country’s engines of growth and a long period of stagnation.

Moments of panic accelerate these shifts. It is as if societies, faced with shock, instinctively search for scapegoats and retreat behind walls and protectionist barriers. Even the pragmatic and tolerant Dutch Republic succumbed to zealotry and xenophobia in 1672, in the face of economic depression and foreign invasion. Power passed to a strongman, and the previous de facto prime minister was not only lynched, but partially eaten.

The ability to retrench in the face of danger is essential. But complex problems are rarely solved through command and control. Trial-and-error approaches and crowdsourced solutions take a little bit longer than having one overconfident leader pointing everybody in the same direction. Replacing the collective wisdom of thousands of local experts with the preferences of one person increases the risk that he points us all in the wrong direction.

Governing for a New Golden Age

At first glance, the governance challenges faced by today’s public sector leaders may seem remote from those of the past. And yet the qualities of great leadership remain surprisingly consistent. Golden age societies had to contend with plagues and invasions: the experience of a global pandemic and renewed geopolitical tensions make some of these recurrent challenges seem strikingly familiar.

Great leaders are most often not those who try to solve every problem themselves, but rather those who create conditions for others to explore, experiment, fail, and thereby discover more sustainable solutions. This requires humility – an acceptance of decentralised knowledge – and also the courage to remove structural barriers that hinder openness and learning. At key moments, leaders have to break deadlocks or dismantle obstacles. They borrow and benchmark, counteracting the “not invented here” mentality. They build institutions that encourage local initiative and information-sharing.

Thriving societies must move, from what Thucydides described as the Spartan instinct to wall oneself off to preserve what one already has, towards the Athenian impulse of being constantly open to acquire something new. Governance in a golden age is not the pursuit of perfection, but the design of possibility.

This delicate balance is embodied in the two most iconic citizens of ancient Athens. Socrates, who was wiser than others because he knew the limits of his own knowledge; and Pericles, who built an optimistic culture by reminding his fellow citizens of their own capacity and agency, assuring them that, if they persevered in courage and ingenuity, “future ages will wonder at us.” We still do.

To learn from the great civilisations of the past does not mean indulging in nostalgia, or imitating their customs. We should not envy what they were but emulate how they looked to the future: as a space of hope and possibility, to be created through learning, adaptation, and discovery.

Heading 1

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

Heading 6

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Unordered list

- Item A

- Item B

- Item C

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Endnotes

- Item 1

- Item 2

- Item 3

Johan Norberg is a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C. He is the author of several best-selling books on history, economics, and politics, including his most recent work, “Peak Human: What We Can Learn from the Rise and Fall of Golden Ages.” He holds a Master’s degree in the History of Ideas from the University of Stockholm.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.